Greyhound Canada has recently announced it is pulling out of Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and BC this year, their senior vice-president in an interview with Canadian Press said, “simply put, the issue that we have seen is the routes in rural parts of Canada — specifically Western Canada — are just not sustainable anymore.” This failure of a business model is sad for those who relied on the service, but is an opportunity for everyone in the transportation industry to reflect on the question, how can we make rural transportation sustainable?

Greyhound blamed lower cost of car ownership and rival transportation services that are subsidized as the main culprit for the struggle to maintain in the region. Probably the answer is that demand for transportation was too low and too sparse for them to continue. Of course the demand is not zero, there are already stories of people who relied upon these routes for medical treatment and businesses that used the buses to move goods throughout the area.

The inter-city bus model is not dead, as seen by the enormously successful “Chinatown” bus companies in the US that have been operating in a grey market for years, without subsidies or regulation. Compared to Greyhound Canada which has been operating at a loss for more than 10 years. Chinatown bus companies do not offer a pure on-demand trip booking experience like a taxi cab would offer, but they did offer something better than a fixed route. The main idea is that they get people to tell them when they need to be somewhere. And the bus service gets enough people close together in the time they need to be there, and gets the bus ready for that trip. Pantonium’s CTO Khun Yee Fung explains:

“For flexible long distance bus service, there are three parameters: who wants to go, where do they want to go, and when do they want to go. The basic idea is to ‘form’ a trip to accommodate as many people going from one city to another city, with enough people to be profitable, both ways, based on the times and location given by potential riders.”

Introducing flexibility in route scheduling can help but the main reason why some long distance services thrive and others fails is the economics of the routes, taking people between big cities that are close together is easy to make profitable, taking people between small communities that are far apart is going to be hard to make profitable. However there are businesses that do this constantly, at extremely low levels of demand using a very different model of pricing, scheduling and service level.

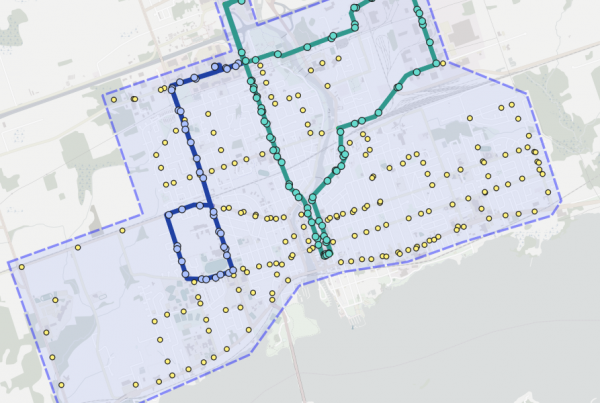

Pantonium provides a technology solution for long distance medical transportation companies across North America, including many city to city transportation companies operating in low density regions. For instance in Idaho there are companies that provide transportation all over the state, they collect hundreds of trips up to the day before. Asking riders for their location, and desired pickup or drop off time at another destination.

This is door-to-door level of service, unlike traditional buses, thus solving the first/last mile problem. Then the company runs a fleet management algorithm on the list of trips to first of all make sure that the entire list of trips can be handled and that all the vehicles are at maximum capacity. Another major difference of this service, one that all bus operators should consider, is the size of vehicles. The transportation providers in Idaho realized quickly that large vehicles are not as economical, even though a big van or a bus can carry more people, and more fares, there is only so much demand and it is spread out and large vehicles cost far more to operate. Procuring smaller vehicles allowed the algorithm to fill more vehicles and cover more ground. This gives better customer service as the fleet can match people’s schedules closer and reduces the cost of maintaining a large fleet.

Having a fleet is important, for low density areas ride sharing like Europe’s BlaBlaCar wouldn’t be reliable and neither would ride hailing services like Uber, due to the challenge of having vehicles always available and keeping drivers where they need to be. An unpaid driver is not going to idle all day waiting for a few fares, nor will there always be a driver willing to share a ride to another city when people require it.

The way forward for rural communities is partner with operators that are willing to use new methods and technologies to provide a reliable service that actually matches demand. Luckily there are still a few months before Greyhound officially pulls out of Western Canada, time enough for interested stakeholders to think about people transportation systems of the future.

Photo credit: Ken – Greyhound 2972