“In America a pedestrian is someone who just parked their car”

When comparing North American populations to Europe we see a stark difference, North Americans do not want to walk. This has been a fact since mass adoption of the car, which drove our infrastructure and culture away from walking. And unless we see $20-a-gallon gas prices there is probably no way we can quickly get people to walk more. This is a health problem, an environmental problem and a problem for public transport. Public transport’s main issue is that people have to walk to get to transit stops, but how can our indolent population access transit when they hate walking?

This has been a question for public transit since the 1970s and while the actual empirical research is hazy, it is a common rule of thumb in public transit discourse that people are willing to walk 0.25 miles or 400m to a bus station. This rule has been extensively researched and applied, with mixed results. Studies of Californian transit users have shown that people “living within one half mile (0.8 kilometers) of a transit station were four time more likely to use transit than those living between one half mile and three miles (4.8km),” they also found that “52.3 percent of previous automobile commuters switched to transit after moving within a half mile of transit stations.” Studies of elderly transit users in suburban Florida have shown that a walking distance of one-eighth of a mile (0.2 km) was 3 times more likely to encourage transit usage than a quarter-mile (0.5km). There is certainly some correlation going on it makes intuitive sense that the usage of transit will increase positively with ease of access.

The obvious thing to do is to plaster populated areas with stations and stops in order to keep as many people as possible in the walking “sweet spot.” This is difficult in marginal areas, where the public transit operators are mandated to provide coverage, but are constrained by the smallness of demand relative to the size of the geography. These could be small towns, rural areas, suburbs and other low density, low demand regions, where vehicle frequency and running times are usually already pushing the boundaries of acceptable numbers. For public transit operations with tight, hard to change budgets putting more stops to decrease the walking times of users is not possible. The result is many people have to walk huge distances just to get to an infrequent bus stop, if they have a choice they will drive.

One solution has been rigorous demand analysis of operational areas to intelligently make sweeping changes to stop locations and routes. Houston’s public transit did this in 2015 with great effect and moderate cost and disruption of their service. This is not a total solution, changing around routes will not solve the basic challenges of geography and limited resources.

Another solution suggested by Australian academics Daniels and Mulley, (their country also suffers from an anti-walking predilection), is to provide “flexible transport services as an access mode to more distant public transport services.” This happens to be our answer as well, flexible transit with dynamic routes and stops is the answer for transit in low density areas. It is not just about better bus routes, or bus rapid transit, or express buses, or increased bus frequency. It is not even about replacing buses with trains or with Ubers. It is about changing the idea of buses, it’s about turning them into a more useful service. Buses are not on tracks, they do not necessarily need to be on arbitrarily made schedules.

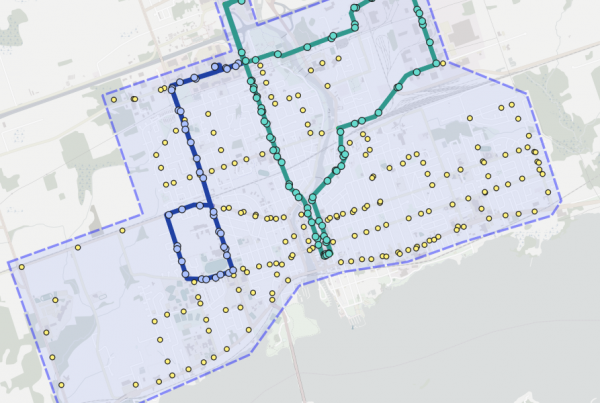

By freeing buses from fixed routes you allow operational flexible in several ways. You could cover the same route area reliably with fewer vehicles, by only dispatching to stops when there is an order from riders. You could also allow route deviation; maintain a “fixed route” with a corridor around it with additional stops that would only be visited by a bus to pick up riders who requested a trip. This is especially important when walking distances are so great as to discourage the use of public transit.

Here is what we have to make it work: bus locations can be easily communicated in real time, their drivers can be guided by GPS and computer aided dispatch systems, riders can contact the public transit through kiosks, phones, and web browsers to get information and request rides to their location. Adding to the “where’s my bus” applications in use today by most public transit operations, but now you can order a bus to come to you. The flexible routes can be coordinated so when you get picked up by one bus you can be taken to another route where a bus will be waiting for you.

Fixed schedules are not always the ideal, it may be easier for operators and users, you set it and forget it and when the buses get full, it is the cheapest way to move masses of people. But when the physical realities of the system make an economic or attractive service impossible it is time to get over our slavish need for fixed routes and to get buses to react to demand in real time, in an intelligent way. If we have learned anything from the last five years of transportation, it is people want their transportation on-demand, they want it to come to them when they need it. Why? Because North Americans hate to walk and that ain’t changing anytime soon.

Image 1: Justin Wolfe – Flickr

image 2: Dennis Jarvis – Flickr

image 3: Brandon Martin-Anderson – Flickr