Like many institutions these days, it has been a challenging time for paratransit. Higher ridership and lower operating budgets have reached the point where experts are saying that the status quo is now unsustainable. The ongoing problem with the service is its regulatory necessity combined with inescapable cost. Providing demand response transportation in specialized vehicles, moving small numbers of people, will be more expensive than conventional transit no matter how or where it is done. From large cities to small, the average paratransit trip costs operators around $30 (USD) compared to $3-$8 for fixed transit. In most cases the rider pays the same standard fare regardless of what level of service they receive. The poor economics of paratransit has led to “ride shedding” where private services have increasingly relied on public services to provide transportation. Organizations that can bear the cost are either subsidized, or rely on insurance plans, or corporate sponsorship, when those sources of funding dry up, it is the riders who end up suffering through service cuts. So what can we do as hundreds of North American paratransit services hurtle towards funding precipices?

The most common ways of cost control in paratransit has been shifting riders to traditional transit. This has been enabled by the new generation of accessible transit vehicles and infrastructure. A key policy tool in this effort has been education of paratransit riders to help them utilize conventional transit. According to Metro Magazine, 56% of transit agencies reported having travel training programs in place and 70% claim the programs helped cut costs by moving more riders to fixed route systems. Another effective tool has been economic incentives such as reduced or free fares on conventional transit for those eligible for paratransit, this is an obvious winner, for example Access Services in Los Angeles saves $26 million annually due to their Free Fare Program, having moved one third of their riders to conventional transit.

Cutting closer to the point, if agencies are going to educate people and help them shift to conventional transit, they need to make it as easy as possible for riders to get to their destination. We then come to a more ambitious solution, the integration of paratransit into conventional transit. Thankfully, after an extensive study, the Transportation Cooperative Research Program created a report on Integration of Paratransit and Fixed-Route Transit Services. Within which they have outlined the various ways that this integration has been done in North America.

Here are the three basic types of integration:

Here are the three basic types of integration:

- Paratransit feeder service exclusively for people with disabilities that feeds into fixed route service. People are picked up from homes and dropped off at the appropriate fixed route stop.

- General public demand-response feeder service that feeds into fixed route service at transit stops. This is the same as above but also open to the public, at least allowing more utilization of paratransit vehicles.

- Route deviation feeder service. Fixed route bus that deviates for people with disabilities and older adults, and connects to the mainline fixed route service. This has the potential to replace all or most paratransit vehicles, depending on how much deviation is possible.

What all these integration types have in common is they help shorten the expensive paratransit component of trips by replacing them with fixed route legs. According to the TCRP the result of feeder service integration is significant savings, this has been seen in large transit organizations like TransLink in British Columbia and Utah Transit Authority and in smaller ones like Pierce Transit in Washington.

What integration schemes also have in common is a major drawback. People do not want to give up their door-to-door paratransit service. If given a choice riders will take the full service option, successful feeder services offer a only a feeder trip or no trip at all, if the feeder trip is possible. This is challenging for most organizations. The TCRP report concluded that, “policy makers and managers at these agencies may be unwilling to take the political heat of offering a paratransit ride that does not deliver the rider to their destination.” Transit agencies should not have to choose between two politically difficult solutions, which is why we have another way.

Hybrid Buses and Paratransit

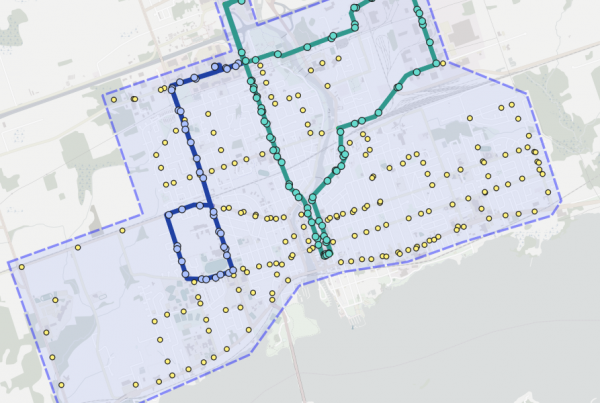

The integration of paratransit into conventional transit ultimately requires the integration of systems and technology on both sides of the service in a holistic manner, this has been lacking in most previous attempts. Even “integrated” systems keep paratransit and conventional operations in respective silos and also keeps rider and vehicle information separate. In an ideal integration scenario, everything will be coordinated centrally and also at a operational levels. What does this mean? Once the central dispatching system knows the location of all vehicles, both fixed route and demand-response, and also the destinations and departure times of its riders, it can build a travel plan using all available vehicles in real-time. The effectiveness of this increases when some buses are taken off their fixed routes, giving more flexibility for coordination, (i.e. a bus waiting an extra four minutes to load a wheelchair) flexibility will also allow less paratransit vehicle usage (i.e. bus deviating its route to pick up a limited mobility rider rather then sending a van). If you are going to run a feeder service of any kind into a bus system, it would be ideal to build some flexibility into as many bus routes as possible. The centralization of information and control of everyday operations allows the system to be more responsive to demand and also more able to communicate to riders and drivers what their potential trips will look like.

In this way all transit vehicles will know where and when to drop off passengers to allow the completion of their trips. This is key, if riders are going to be pushed to conventional transit the level of service should decline as little as possible. In terms of cost, we are fortunate that paratransit is such an insatiable money pit that reducing the vehicle time needed for that service will likely pay for introduction of a modest flexible bus service. These changes would also make the service more useful for the general public who could, if agencies desire, use paratransit vehicles as a first and last mile solution. Once new technology is allowed to impact transit operations the opportunity for new service models opens up, while still maintaining the service levels people have come to expect. If you know of a public transit system that is considering drastic changes its paratransit and buses to maintain viability, let us know at info@pantonium.com for a consultation; there might actually be a way to make it great again.