Microtransit Won’t Deliver Efficiency to Ontario Cities

By: Gurjap Birring

Transit agencies across Ontario, still reeling from ridership that hasn’t bounced back even as cities have reopened, recently got hit with stiff news from the provincial government.

While the federal and provincial governments have earmarked some $2 billion in funding for transit agencies to help fill their budget shortfalls, the second phase of funding due in 2021 will come with conditions.

In a letter dated August 12, Ontario Transportation Minister Caroline Mulroney has suggested that cities will have to evaluate low-performing bus routes and think about replacing them with microtransit services.

Microtransit generally refers to transportation delivered by vans or minibuses that riders book trips on via mobile apps. Operating similar to UberPool or a taxi service, but riders are sometimes matched onto the same shared vehicle to complete their respective trips.

Why is the Government Suggesting Microtransit?

The provincial government says it is imposing these conditions to ensure the sustainability of public transit beyond the current term for emergency funding, due to expire March 31, 2021.

Christina Salituro, spokesperson for the Ministry of Transportation, told Daily Hive that “Microtransit, or providing right-sized transit, could be a more sustainable way to provide transit service to unserved and underserved areas across the province, hence its being a key provincial interest,”.

The province seems to believe that by shifting transit riders onto smaller vehicles running on-demand, transit agencies will be able to provide adequate service while reducing operating costs. Trying to achieve those outcomes with microtransit, which some tout to provide service more cost-effectively than fixed routes, may be a fool’s errand.

Microtransit Often Has Key Shortcomings

While the province hopes transit service can be delivered more efficiently and cost-effectively through microtransit, projects operating in other cities point to those goals being met in very specific applications.

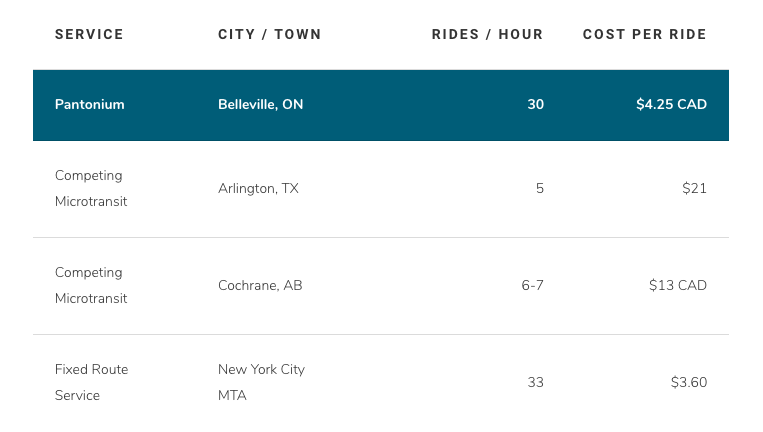

In North America, the least productive fixed route buses achieve about 10-15 rides per service hour. In comparison, a microtransit pilot launched in Calgary, AB last year, which claimed to achieve “industry best vehicle productivity”, reported 6 rides per service hour.

This service covered a neighbourhood that had no existing public transit and dropped riders to only two transit hubs in an adjoining area, which connected riders with the wider transit system. It operates as a first-mile/last-mile service for a small rider base and covers a limited geographic area. Microtransit works in specific situations like this, but struggles to find more broad application and provide long term usefulness.

As ridership rises, microtransit would require more and more vehicles to service demand and thereby erode any previous efficiencies. If ridership recovers to sufficient levels, fixed route buses will deliver better productivity and municipalities will wisely switch back. Of all the levels of ridership that a fixed route doesn’t service efficiently, microtransit is only productive on the lower end.

Looking at other microtransit services pre-COVID19, one launched in Sacramento, CA which was deemed a “success”, was generating only 3.24 rides per service hour in May and June of 2018. Newark, CA which switched their fixed-route service in favour of microtransit in 2017, saw overall ridership decrease by 20%.

Whether handling ridership at current pandemic levels or ordinary volumes, when fixed routes aren’t productive, there is an alternative on-demand service that delivers better productivity broadly across different ridership levels. It’s called Macrotransit.

Taking up Macrotransit Brings Better Results

Macrotransit is also an on-demand service, but crucial differences from microtransit allow it to deliver better productivity and performance in a larger number of circumstances.

The essential distinction of Macrotransit is its self-adjusting system that dynamically routes buses in real-time based on rider demand. Because the entire fleet’s routing is continuously being optimized for efficiency, it results in productivity levels far higher than microtransit.

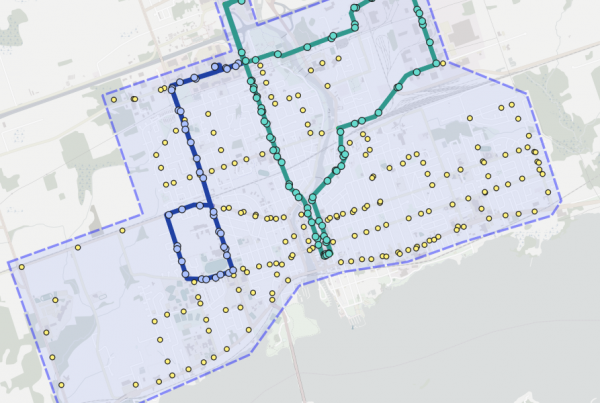

Macrotransit service deployed by Pantonium in Belleville, ON achieved 30 riders per service hour, an increase in ridership of 300%, and service area expansion by 70%.

While microtransit usually requires transit agencies to use small vans or shuttles, Macrotransit delivers on-demand service using the transit agency’s current bus fleet. By using full sized vehicles, Macrotransit can match fleet capacity to fluctuating ridership, and still drive efficiency across a broader spectrum of ridership.

Pre-COVID19, Belleville produced positive operational and social results (a survey indicated increased social inclusion), but when the pandemic hit, Macrotransit delivered remarkable utility. Belleville lost most of its ridership, but, unlike other cities, it had the tools to swiftly adapt its entire transit system to go on-demand. They continued to provide ample service for essential travel, yet did so cost-effectively.

Put plainly, Macrotransit delivers to cities performance that optimally uses their transit resources while equipping them with the versatility to provide great service in a whole array of circumstances.

The province wanting cities to pursue more sustainable methods of delivering public transit is understandable, especially in light of ongoing economic and social uncertainty. However, it is vital that civic leaders pursue solutions that allow them to do more with less. Now more than ever, cities must build transit systems that are productive, adaptable, and resilient.