Rural Transportation Challenges: Death of an Idahoan Transit

By: Luke Mellor

What happens to a public transit when it is cut off from funding? In the case of Targhee Regional Public Transportation Authority in Idaho the last month the agency’s board of directors had no choice but to dissolve the entire service, fire its employees and liquidate all assets, leaving thousands of riders stranded. This is an extreme example of public transit attrition. It seems that the direct cause of this acute failure was a funding shortfall caused by the Federal Transit Administration and Targhee’s city council declining to provide further cash to the TRPTA due to their failure to provide paperwork and respond to federal audits. This was exacerbated by the US government shutdown earlier this year. Ironically the federal government will end up paying to transport some of those riders anyways. As many of TRPTA’s riders used public transit to access healthcare and these vulnerable riders are now being directed to Idaho’s non-emergency medical transportation services, which is privately contracted to MTM and paid for by state and federal Medicaid dollars.

The death of this rural transit, though dramatic, does show how delicate our transportation systems are to attrition. All it takes are a few years of declining ridership and tepid external funding rounds to send a transit into a death spiral. Rural transit is especially vulnerable to this. Considering the geography that it is required to provide service to. Rural areas cover 97% of US land area but contain roughly 19% of its population. This means that all hope for favorable fare recovery is lost because vehicles have to travel further to pick up fewer people. The geography also reduces the effectiveness of active mobility like walking or bike riding.

Rural areas also have a population that is aging faster. The median age is 43 in rural areas compared to 36 in urban areas – and 17% of rural residents in the US are 65+ (compared to 14% in urban areas). Additionally, there is a higher percentage of individuals with disabilities (17%) in rural communities compared to urban areas (14%). Roughly 31% of rural communities are either elderly or disabled, and are often two demographics within a community that need reliable transportation services the most. A transportation network that does not meet the mobility needs of these individuals marginalizes them from their society, contributing to that communities’ stagnation and reducing overall well-being.

It is not all bad news, for lack of better options, rural transit ridership per capita increased 8.6% between 2007 and 2015. Despite this increase in ridership, 40% of rural residents report living in counties with no public transportation services. This speaks volumes to overall under-utilization of transit resources within municipalities, and that transit supply is not being efficiently matched to rider demand.

A 2016 transportation study conducted by the US Department of Transportation found that 37% of respondents had personal access to a vehicle, 54% relied on rides from friends and family, and 30% relied on public/paratransit. Of this 30%, 50% of them noted that they routinely had to wait more than 30 minutes for a ride – even while using demand response services.

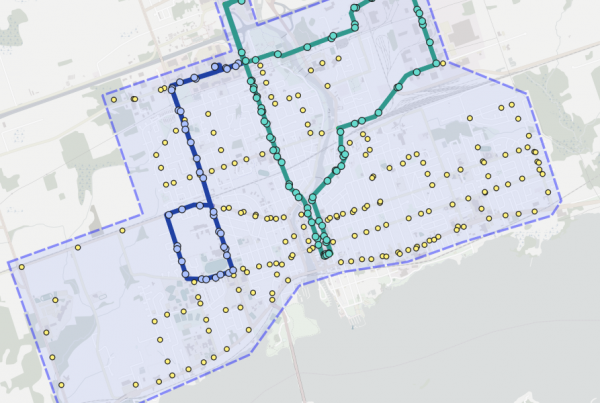

It is impossible to replicate the high efficiency of dense urban transit services in these rural areas. As the combination of economics and geography prevents the operation of highly productive fixed route transit. These challenges are not new, for the past 100 years public transit agencies have been trying to overcome them. With the implementation of an on-demand transportation service model, municipalities can alleviate some of the inefficiencies that are caused by operating a rural fixed-route model. This approach to public transit is not new, demand-response transit, most of these on-demand transit solutions are not sufficient to drastically change the challenges of public transit.

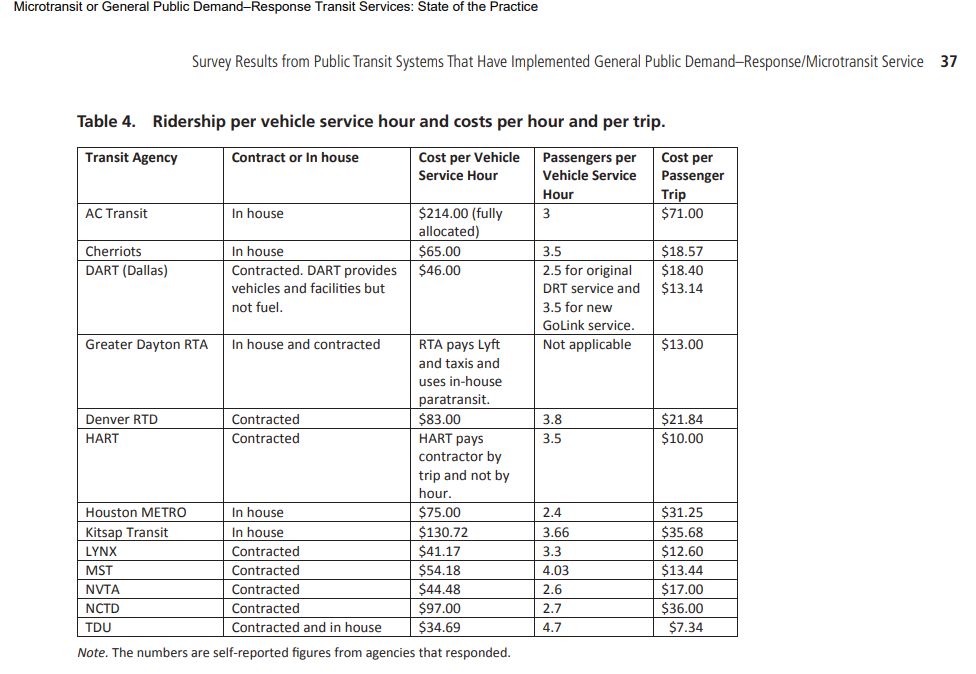

As we have seen in this new report by the TRB on recent microtransit projects even “cutting edge” technology providing on-demand transit in a variety of geographies cannot come close to even the most unproductive fixed route in terms of riders per hour or cost per service hour.

TRB’s Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Synthesis 141: TCRP Synthesis 141: Microtransit or General Public Demand–Response Transit Services: State of the Practice

To put the above numbers in perspective, even the worse fixed bus routes in rural areas generally average 7-14 riders per revenue service hour and are similar in cost per hour because drivers, not vehicles are the most expensive part of service delivery. Pantonium has been able to get on-demand bus ridership to average between 20-30 riders per revenue service hour in Belleville Ontario, however that was with a very new operational model that used full sized buses that only traveled stop to stop, based on rider demand.

Our hot take on the state of rural public transit:

- Public transit needs a steady and reliable source of funding to sustain new mobility initiatives, not just grants

- More technology and operational changes that are actually innovative and trying to move the dial on performance

- Marketing, education and training of riders to change behaviours to get people out of their cars and on to public transit

Events like the death of an entire public transit agency do not happen often but if there are a series of technological, economic and political disruptions in the future (which there always are) there may be more catastrophic failures of even larger transit agencies. We might not notice when it happens in rural Idaho but we will certainly notice it in major urban areas. These are the stakes that we must consider when deciding when and where to make changes to the systems that move us every day.