Transportation network companies (TNCs) have been spreading across the world as fast as billions in speculative funding can propel them. The jury is still out if this is good or bad. Taxi drivers will be quick to denigrate Uber and its ilk, average people either enjoy and use the service or don’t use it and don’t care, and politicians are, as usual, out to lunch. In Pantonium’s home city, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) are still collectively scratching their heads, spending a whole quarter of 2016 writing a report weighing the “risks and benefits” of TNCs. In a recent interview with Wired Magazine, Paul Lewis, vice president of policy and finance at the Eno Center for Transportation summed up the current policy challenge facing public transit operators, “There’s this outstanding question as to whether these new shared mobility services are complementary to public transit or competitive.” In the past few days there has been new examples of these TNCs trying to be complementary services to public transit, essentially solving the last mile problem, or service gaps in under served times and areas.

There is a more fundamental change in our transportation habits caused by TNCs, just this month the American Public Transportation Association released an excellent research paper called Shared Mobility and the Transformation of Public Transit, some of their key findings were that:

- The more people use shared modes, the more likely they are to use public transit, own fewer cars, and spend less on transportation overall.

- Shared modes complement public transit, enhancing urban mobility users substitute more for automobile trips than public transit trips.

- While a number of regulatory and institutional hurdles complicate partnerships in this area, technology and business models from the shared mobility industry can help drive down costs, increase service availability and improve rider experience.

But this is not the whole story. We would like to suggest that public transit operators have a duty to provide effective and equitable service to the public, and that would be undermined by standing idly by as TNCs innovate and expand into markets traditionally served by public transit. There are two main reasons for this contrarian position.

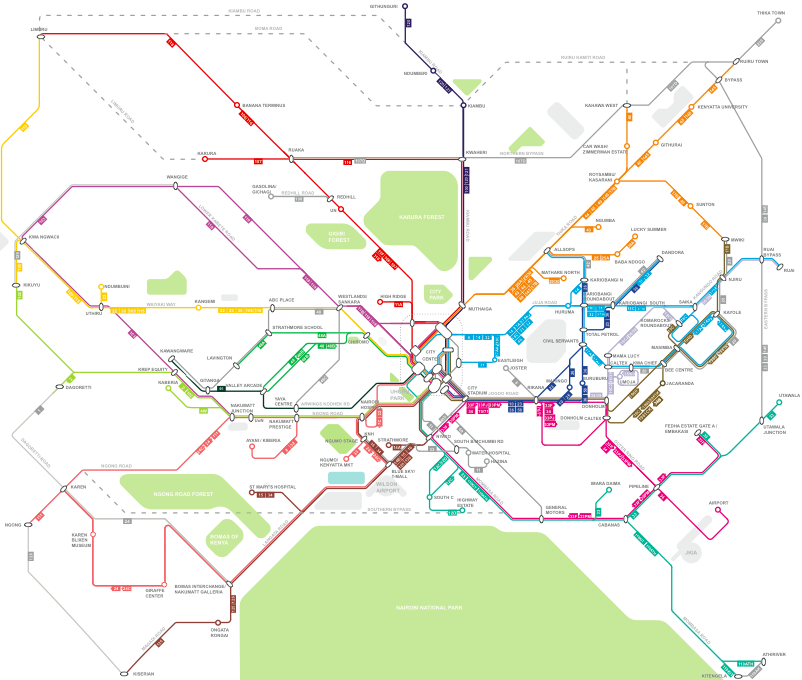

You cannot expect TNCs to do what is in public transit’s interest, ie. feeding people into the routes designed and served by public transit. TNCs will follow the money, not a plan. A good example of this are the informal, private, for-profit, van taxis that operate in most developing countries. They are called matatus in Nairobi, Kenya, we did a piece on their South African cousins the kombis taxi last year. In Nairobi the matatus have self-organized into an orderly system of routes, which were lovingly mapped out by the Atlantic City Lab. The issue of the matatu van service, as pointed out by transit blogger and consultant, Jarrett Walker, is that “every matatu wants to go downtown because it’s the biggest market, and a mutatu driver doesn’t have to be coordinated with anyone else to fill a bus going to and from there.” The result of this laissez-faire system are constant traffic jams of mutatus rushing downtown and “a single market over served and other markets under served.” Public transit will have to use some sort of carrot or stick to ensure that TNCs actually compliment their own service, because the market probably won’t.

The second issue for public transit and TNC cooperation is equity of cost, this has obvious implications for fairness but also precludes public transit ever winning in a direct competition with TNCs. Research has shown that the incomes of those using ridesharing services are almost 70% more than the median wage, it is no surprise that the major criticism of Uber is that it is ultimately a service for the affluent. Should the TNCs continue to grow in breadth and depth and begin to supplant and replace transit the result could be a decline in affordable transport for the poor. This is of course merely a speculation, trends could change, but it is the current course of many North American cities. Just this week the TTC announced it is on pace for a $30 million (CAD) shortfall in 2016 due to declining ridership.

This is a little more complicated though, ridesharing services, if they actually manage to share rides, can be quite cheap: between $5-10 for a normal shared ride. This is not as affordable as traditional transit, but it is as close as technology and the market can make it. It is doubtful that public transit could offer a similarly priced service and not lose money. Uber does not own the vehicles in its fleet, and its drivers are all self employed “contractors”. Public transit, on the other hand, has to maintain its own fleet and cannot exploit employees so flagrantly. Jarrett Walker sums up the challenge for economically providing this type of service:

“Another way of describing all of the ‘demand responsive’ or ‘Uberization’ fantasies is that they are predicated on moving large amounts of steel and rubber per customer trip, compared to big-vehicle fixed-route transit. Even without considering the economics of labor, this can only be less efficient, in terms of energy and urban space, then what crowded big-vehicle transit achieves”.

The implications of his argument are simple, the economics of transportation will silo TNCs and public transit into their own separate service types with little overlap, neither service should attempt to do what the other is doing.

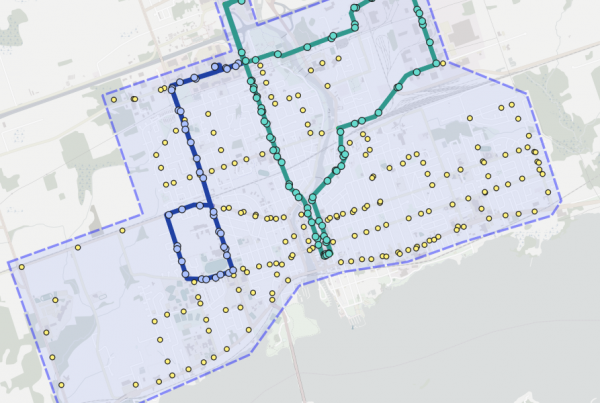

I take issue with this conclusion; it is myopic and it allows public transit authorities to stick their heads in the sand and ignore developments in the capabilities of transportation technology. There is possibility for a synthesis of the best parts of the TNC demand response model and the efficiency of the public “big vehicle transit”. The basic idea is to free buses from their fixed routes, using the same type of technology and customer service face that has made TNCs the darling of consumers. A detailed explanation of the system we are proposing can be found in this blog post, and next week we will look at the cost of such a system and see if it is economically feasible. Cost is the crux of the problem that public transit faces, but if they can develop new methods of service that are profitable and better than TNCs, then everyone can reap the benefits of progress, not just the affluent.

Feature image: digitalmatatus/Civic Data Design Lab MIT